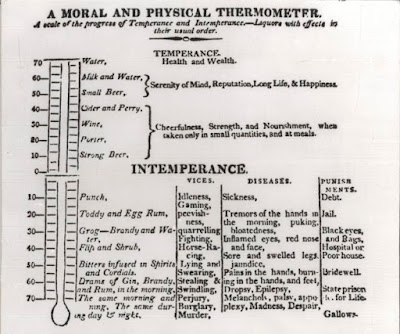

Go ahead, have a small beer; it will bring “Serenity of Mind, Reputation, Long Life, & Happiness.” Even a strong beer would be fine, for that brings “Cheerfulness, Strength, and Nourishment,” as long as it’s only sipped at meals. So declared Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the early republic’s most prominent physician. In his loquaciously named pamphlet, An Inquiry Into the Effects of Ardent Spirits on the Human Mind and Body, first published in 1784, Rush describes the “usual” downward spiral of drink. What starts as water and wine quickly turns into punches and toddies and cordials, ending with a hopeless vortex of gin, brandy, and rum, “day and night.”* In the pits of intemperance, one can expect such vices as “Idleness, Gaming, peevishness, quarrelling, Fighting, Horse-Racing, Lying and Swearing, Stealing and Swindling, Perjury, Burglary, [and] Murder,” with punishments including “Black eyes and Bags,” “State prison for Life,” or, worst of all, “Gallows."For once, I'll listen to the doctor. Just beer for me, I'll leave the whiskey to others.

Why did this 18th-century doctor care so much about moral consequences of drinking? “It was a pretty common belief among the founders [regarding] America’s experiment with republicanism, that the only way that we were going to keep it was through the virtue of our citizens,” said Bruce Bustard, the curator of a National Archives exhibit on American alcohol consumption. As Rush observed the effects of alcohol consumption, he had the young nation’s future in mind: People experiencing what he saw as the “Melancholy,” “Madness,” and “Despair” of intemperance surely wouldn’t make for very good participants in democracy.

Early America was also a much, much wetter place than it is now, modern frat culture notwithstanding. Instead of binge-drinking in short bursts, Americans often imbibed all day long. “Right after the Constitution is ratified, you could see the alcoholic consumption starting to go up,” said Bustard. Over the next four decades, Americans kept drinking steadily more, hitting a peak of 7.1 gallons of pure alcohol per person per year in 1830. By comparison, in 2013, Americans older than 14 each drank an average of 2.34 gallons of pure alcohol—an estimate which measures how much ethanol people consumed, regardless of how strong or weak their drinks were. Although some colonial-era beers might have been even weaker than today's light beers, people drank a lot more of them.

Monday, June 29, 2015

Heeding the Doctor's Advice

The Atlantic takes a look at alcohol-related medical advice of Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment