There are many reasons to be glad that Blake Snell—23 years of age, lately and currently of the Durham Bulls and recently of the Tampa Bay Rays—made his major league debut last weekend at Yankee Stadium. For one thing, it's great news for everyone in the Snell family: Blake, parents Dave and Jane, and brother Dru. For another, it's great for baseball fans: he's a good kid and will be fun to watch. All that can be safely filed under "Things That Are Good."The crazy part is, the players' union is complicit in this crock of shit. I remember Bryant spending a few weeks in the minors last year, but I didn't realize why he did. What a bunch of corrupt bullshit.

But it's also great news for the Rays, and not just because Snell is more likely than not to become a very good major league pitcher. No, it's good news for the Rays mostly because by calling Snell up for a start on Saturday instead of on, say, Friday, Tampa Bay guaranteed themselves, by dint of what can only be described as "service time fuckery," an additional year of Snell's services at a severely and artificially discounted price...

Here's the first thing you need to know: a "year" in the crazy, messed up world of big-league contracts isn't really a year in any normal sense of the word. A year in big-league service time actually corresponds to 172 days spent on a big-league roster, which is a few days shy of the 183 that make up an MLB season. And years of service time are important, because the collectively bargained agreement that governs the sport's labor practices dictate that a player's original team holds exclusive rights to his services for the first six "years" of his big-league career. Except, remember, not normal years. Stupid, bullshit, service-time not-quite-years.

That gives teams every incentive to game the system and keep service-time down during what we normal humans would call a player's first year. Why the hell wouldn't they? Keep a kid under 172 in his first year and you get another one tacked on to the end of the six you already had. Sure, there are rules saying you can't keep a player down for service time reasons alone, but unless execs are dumb enough to email each other saying that's what they're doing, those rules are basically impossible to enforce; this is how Kris Bryant spends a few weeks working on his defense (or whatever) at Triple-A before becoming Rookie of the Year. And, for Snell, a second relevant rule comes into play: if a player spends fewer than 20 days in the minors during the course of a season, whatever time he spends there is retroactively added to his big-league service time for that year.

So if the Rays had called Snell up on Friday, which was the 20th day of the season, rather than on Saturday, which was the 21st, he would have had all his time in Durham at the beginning of the year applied to his service clock, and thus would have been that much closer to achieving the key number of 172 in 2016. But since he was called up on Saturday, it's not a problem. The deadline has to fall somewhere, but the sketchiness is seldom this plain.

By calling him up literally not one day earlier, the Rays guaranteed that Snell, regardless of how much time he spends in the majors going forward—and he was returned to Durham immediately after the start, and so may have to wait a minute for his next shot—can accrue no more than 163 days of big-league service time in 2016; his free agency has already effectively been delayed by one year, from 2022 to 2023. Convenient how he turned out to be ready for the majors on a very day that was most profitable for his ownership group. The same misfortune befell Bryant last year. Funny world.

Monday, May 2, 2016

What a Scam

VICE Sports:

Indiana - The Southern State in the Midwest

Well, except for Missouri (which wasn't part of the Northwest Territory). Here's Fiverthirtyeight on why Indiana is weird:

In 1850, census canvassers started asking Americans where they’d been born, and by looking at state residents who were born in the U.S. (but not in their current state), we can see just how much Indiana stood apart from its neighbors in the Old Northwest. Let’s start with people born in New England, the “Yankees” widely considered to be better educated and more ambitious than their peers. In 1850, only 3 percent of Indiana’s U.S.-born residents hailed from New England. (The Old Northwest average was 10 percent.) Only 20 percent of Indiana’s U.S.-born residents hailed from Mid-Atlantic states such as Pennsylvania and New York. (The Old Northwest average was 42 percent.) But a whopping 44 percent of Indiana’s U.S.-born residents hailed from the South — easily the highest percentage in the Old Northwest, where the average was 28 percent.1Or, to put it another way, Indiana didn't end up with its fair share of Catholics and Lutherans. Also, not surprisingly, Indiana ranks third amongst states for demographics most like America in the 1950s, just behind Kentucky and West Virginia.

Just as important as their numerical advantage, the Southerners got to Indiana first and thus dominated its early politics. (At the state’s constitutional convention, 34 of the 43 delegates hailed from below the Mason-Dixon Line.) They created its local culture, shaping everything from what Hoosiers ate to how they worshipped. (Southerners imported their Baptist and Methodist beliefs, and in the 1850 census 60 percent of Indiana churches belonged to those denominations.) More than any other Midwestern state, Indiana ended up with a certain kind of citizenry: white, working-class Protestants with Southern roots.

And the thing is, it never really changed. Consider the wave of immigration that defined America starting in the 1880s. Indiana had always been the least diverse state in the Old Northwest. And yet, even after millions of Europeans arrived by steamship, were processed at Ellis Island, and scattered across the country, Indiana still featured a foreign-born population of just 3 percent. (The Old Northwest average was approaching 20 percent.) Or consider the rise of the modern city. In 1920, Chicago’s population was 2.7 million; Cleveland’s was 800,000. Indianapolis’s, by contrast, was only 314,194. But Indianapolis wasn’t just smaller — it was more provincial, less vibrant, a city with a population that was only 3 percent African-American and 70 percent native-born and white. (In Chicago and Cleveland, the share of native-born whites was about 25 percent.)...

Among its Old Northwestern peers, Indiana ranks last in median family income. It ranks last in the percentage of residents who’ve completed a bachelor’s degree. It ranks first in the share of the population that is white Evangelical Protestant and in the share of residents who identify as conservative. On these and a host of other measures — percentage of homes without broadband internet, rate of teen pregnancy, rate of divorce — you’ll often see Indiana finishing closer to Kentucky or Tennessee than to Ohio or Wisconsin. In other words, you’ll see 200 years of history making its presence known.

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Twins Days - A Short Doc

Twins Days | A Short Doc from Alex Markman on Vimeo.

NASA Photo of the Day

April 28:

A Dust Angel Nebula

Image Credit & Copyright: Rogelio Bernal Andreo (Deep Sky Colors)

Explanation:

The combined light of

stars along the Milky Way

are reflected by these cosmic dust clouds that soar

some 300 light-years or so above the plane of our galaxy.

Dubbed the

Angel

Nebula, the faint apparition is part of an expansive complex

of dim and relatively

unexplored,

diffuse molecular clouds.

Commonly found at high galactic latitudes, the dusty galactic cirrus

can be traced over large regions toward the North and South Galactic poles.

Along with the refection of starlight, studies indicate

the dust clouds produce a faint

reddish

luminescence, as interstellar

dust grains convert invisible ultraviolet radiation to visible red light.

Also capturing nearby Milky Way stars and an array of

distant background galaxies, the deep, wide-field 3x5 degree

image spans about 10 Full Moons

across planet Earth's sky

toward the constellation Ursa Major.

Image Credit & Copyright: Rogelio Bernal Andreo (Deep Sky Colors)

Why Is That S-Curve There?

From Wired:

While playing with Google Maps, he noticed that much of the Midwest is made up of colorful squares outlined by straight roads that are broken up every 24 miles or so by a sharp jog to the left or right. Ruijter found them so fascinating that he made them the subject of a photo series, Grid Corrections.That stuff is even more complicated than it sounds. I've posted on the rectangular grid system a few times in the past, and that's because it fascinates me and shapes the world I live in.

These kinks in the road date to the earliest days of the US. After the American Revolution, the bureaucrats of the Surveyor General’s office faced the daunting task of parceling out vast swaths of land they’d never seen. To open western territories like Kansas to settlement, surveyors divided land into 160-acre plots—plenty of room for a family to settle and farm comfortably, says Steven Schrock, a civil engineer with the University of Kansas.

It being the Age of Enlightenment and all, the surveyors relied upon orderly and logical straight lines that intersect at 90-degree angles, forming the grid that the Midwest is known for.

There’s one problem with that: The world is not flat. Its oblate spheroid shape has long vexed cartographers, who must often distort reality to make it fit into a functional, two-dimensional survey. But those little fudges catch up with you when you build roads based on those maps. “If you put enough squares on a (more or less) spherical Earth, eventually you have to offset the boundaries so that you end up with what [de Ruijter] is calling ‘grid corrections’,” Schrock says.

Uncorrected, this problem does things like make Greenland the same size as Africa on a Mercator map. Those early American surveyors wanted to make each plot the same size IRL, so they inserted border corrections. When communities laid roads along the borders of these plots, they made those small kinks a little larger so horse-drawn wagons could navigate them more easily. The arrival of the automobile required making them larger still, because cars are faster than horses.

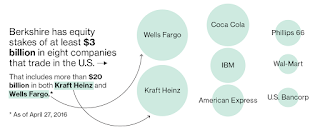

Berkshire Hathaway By The Numbers

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)